In the human genome, only 1.5% of our 3.2 billion base pairs of DNA codes for proteins. For a long time evolutionists though the other 98.5% was “junk” DNA: DNA that was preserved in the genome, but had no function; the byproduct of billions of years of aimless mutations. Over the past seven years, however, scientists keep discovering more and more function for this “junk.” For example, it has been discovered that ~90% of our genome codes for RNA products. Junk DNA also:

- Regulates DNA replication

- Regulates transcription

- Marks sites for programmed rearrangement of genetic material

- Influences the proper folding and maintenance of chromosomes

- Controls the interactions of chromosomes with the nuclear membrane

- Controls RNA processing, editing, and splicing

- Modulates translation

- Regulates embryological development

- Repairs DNA

- Aids in fighting disease[1]

And now, biologist Richard Sternberg has brought my attention to a very interesting find related to a specific kind of “junk” DNA called Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements (SINEs). SINEs are mobile DNA that can insert themselves in various locations within the genome, and are thought to be functionless according to evolutionary biologists.

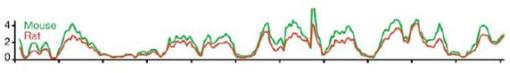

The rat and mouse are said to have diverged from one another 22 million years ago. Since that time, each is thought to have experienced hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of SINE insertion events. Given so many insertion events, we would expect for the location of SINEs to be very different in the mouse genome than in the rate genome (in the same way we would expect a moon that split in two 22 million years ago to evidence a very different asteroid bombardment pattern on its surface). And yet, when we compare the location of SINEs in the mouse and rate genomes this is what we find:

They are virtually identical! This is not what we would expect from a degenerative process like mutations and random insertions over millions of years. We would expect radical divergence, not a nearly-identical pattern. While the SINE sequences are not the same in the rat and mouse genomes, the placement of the SINEs is nearly identical (and they are concentrated in gene-coding regions of the genome).

How do we account for this pattern? Can it be the result of a degenerative process? Surely not. Patterns are indicative of design, and hence purpose. Contrary to the expectations of evolutionary biologists, SINEs do have purpose and function, even if we are only beginning to understand them.

[1]Stephen C. Meyer, Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design (New York: Harper One, 2009), 404-7.

Share your thoughts....