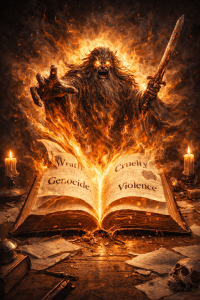

Christians and Jews believe the God of the Bible is morally good. Many non-believers, however, think otherwise. They claim the God of Christianity is morally evil, and thus no God at all. So is the Biblical God the epitome of moral perfection, or a moral monster?

Christians and Jews believe the God of the Bible is morally good. Many non-believers, however, think otherwise. They claim the God of Christianity is morally evil, and thus no God at all. So is the Biblical God the epitome of moral perfection, or a moral monster? Apologetics

February 13, 2026

Divine Sins? Is God a Moral Monster?

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Atheistic objections, Bible Difficulties, TheologyLeave a Comment

Christians and Jews believe the God of the Bible is morally good. Many non-believers, however, think otherwise. They claim the God of Christianity is morally evil, and thus no God at all. So is the Biblical God the epitome of moral perfection, or a moral monster?

Christians and Jews believe the God of the Bible is morally good. Many non-believers, however, think otherwise. They claim the God of Christianity is morally evil, and thus no God at all. So is the Biblical God the epitome of moral perfection, or a moral monster? January 9, 2026

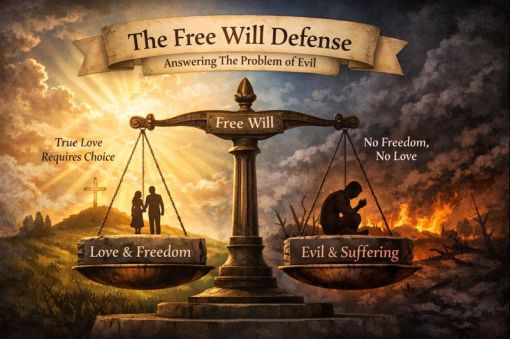

Is the Free Will Defense Fatally Flawed? And Why Won’t Christians Sin in Heaven?

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Atheistic objections, Determinism, Problem of EvilLeave a Comment

My series on the problem of evil will be wrapping up soon. The last two episodes (186-187) have focused on a potential flaw in the Free Will Defense (FWD), which is arguably one of the best answers to the problem of evil.

My series on the problem of evil will be wrapping up soon. The last two episodes (186-187) have focused on a potential flaw in the Free Will Defense (FWD), which is arguably one of the best answers to the problem of evil.

The FWD assumes that it is logically impossible to create free creatures who are incapable of freely choosing evil and hate. However, God is free and God can love, but cannot choose evil. So not only is it logically possible to be both free unable to sin, but it’s a metaphysical reality as well. It would seem, then, that God could have created us both free and unable to sin. If so, the FWD fails.

I examined the objection in great detail, and ultimately conclude that the objection fails and the FWD succeeds. If you want to know why, listen to the two episodes wherever you get podcasts or at https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com. Or, you can read the paper I wrote on the topic below.

If none of that interests you, perhaps you will be interested by my discussion of why Christians will not sin in heaven – also covered in the podcast and paper. What does that have to do with the FWD? Listen to episode 187 or read the paper to find out.

A Potential Flaw in the Free Will Defense

July 30, 2025

I posed a moral dilemma to a few Christian thinkers, but none were able to provide a fully satisfactory answer. While I think most ended up at the right conclusion, no one could really articulate the moral principles used to come to that conclusion. So I thought I would pose the dilemma to AI and see what it had to say. Could it provide any additional insights into Christian moral reasoning? I chose to use ChatGPT and Gemini. I will reproduce the chats below for your reading pleasure, but I would like to make several observations first.

I posed a moral dilemma to a few Christian thinkers, but none were able to provide a fully satisfactory answer. While I think most ended up at the right conclusion, no one could really articulate the moral principles used to come to that conclusion. So I thought I would pose the dilemma to AI and see what it had to say. Could it provide any additional insights into Christian moral reasoning? I chose to use ChatGPT and Gemini. I will reproduce the chats below for your reading pleasure, but I would like to make several observations first.

July 25, 2025

Pro-lifers don’t think abortion is that big of a deal

Posted by Jason Dulle under Abortion, Apologetics, Bioethics[2] Comments

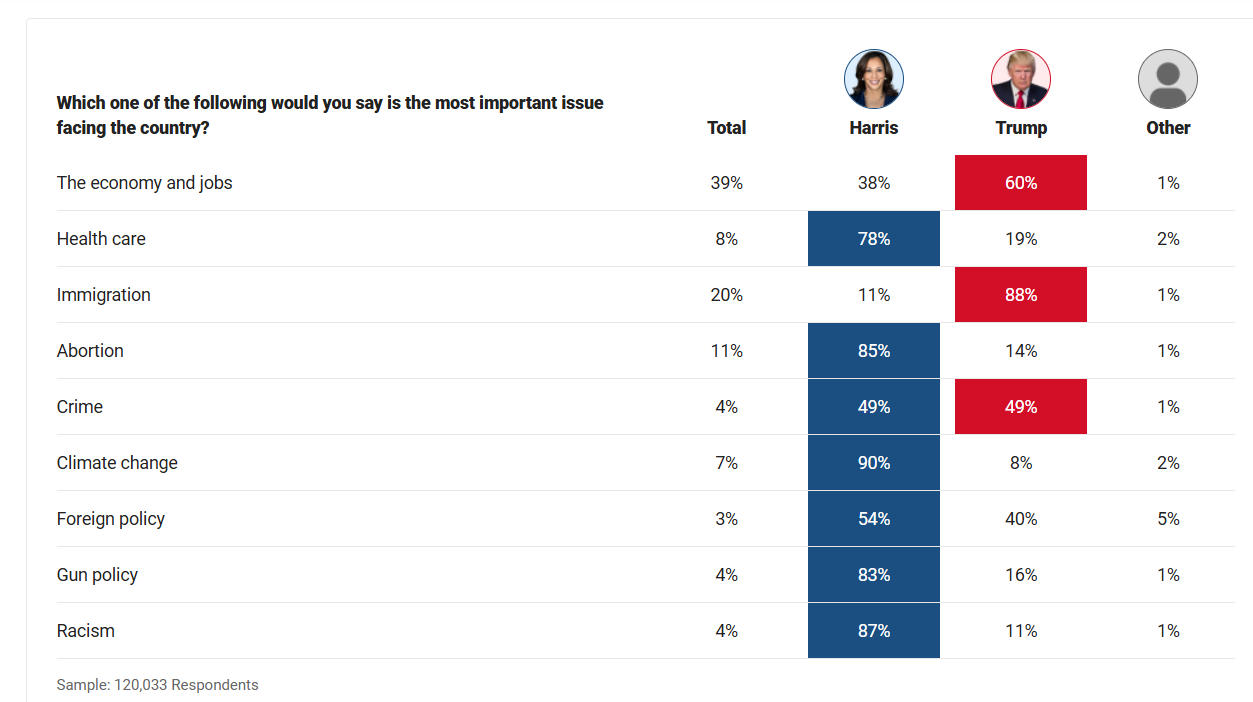

One of the things I find most frustrating is the fact that most conservatives in America don’t consider abortion an important issue, particularly when it comes to how they vote in the political realm. Fox News, in partnership with the Associated Press, issued a 2024 voter analysis that reveals just how little Republicans care about the abortion issue. Consider the following data points:

- Only 11% of Americans considered abortion to be the most important issue facing the country. Ironically, 85% of those who considered it to be the most important issue voted for Kamala Harris. In other words, the vast majority of the 11% who considered abortion to be the most important issue in America are for abortion, not against it. Only ~2% of Republicans considered abortion to be the most important issue facing America this election:

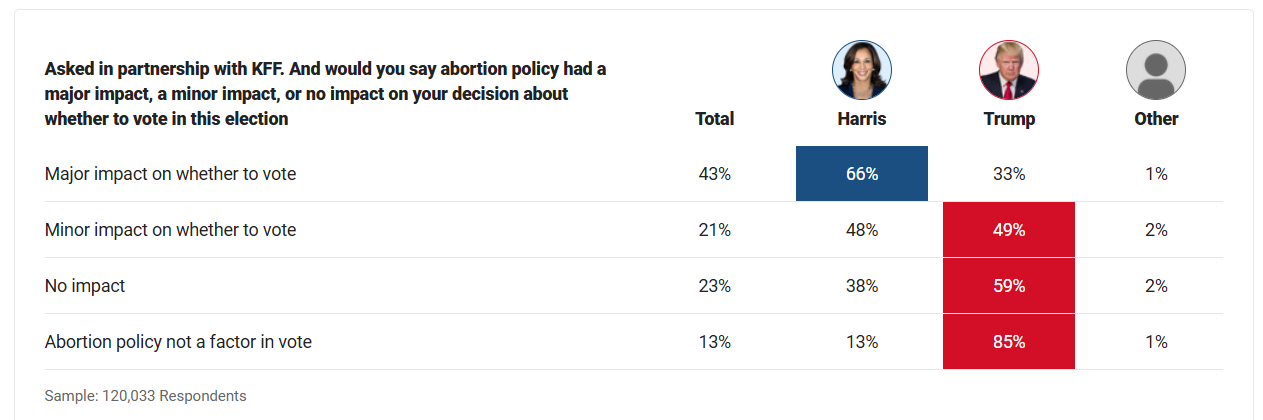

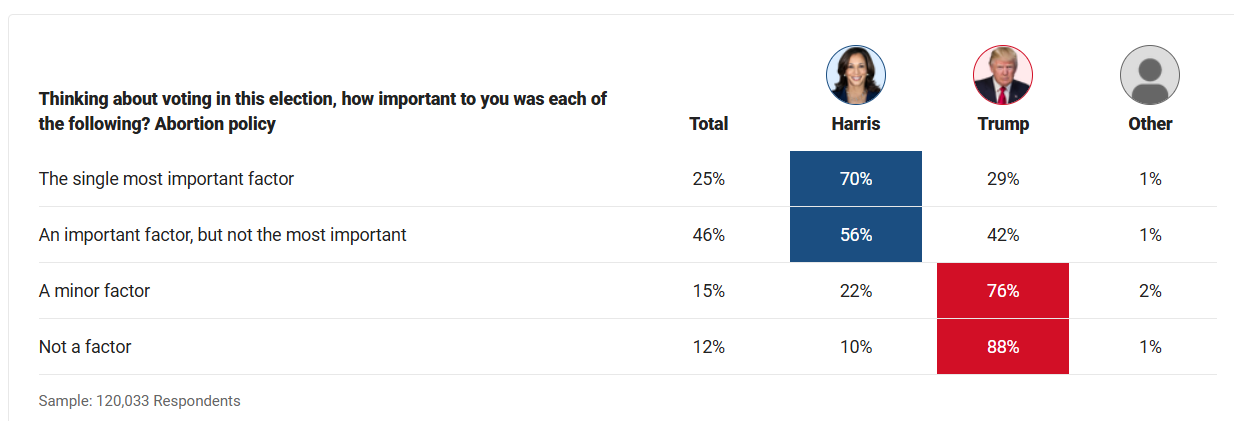

- Not surprisingly, the issue of abortion caused more Harris supporters to vote in this election than Trump supporters:

- When asked specifically about how important abortion policy was to their vote, 27% of Americans said it was either not a factor or only a minor factor. More than ¾ of that 27% cohort were Trump voters:

- While Trump voters do not consider abortion to be that important of an issue, they are much more likely to think government policy should be pro-life. More than 1/3 of Americans think abortion should be illegal in most or all cases. Trump voters make up ~82% of those who take that position. This means that while Trump voters are more likely to think abortion should be illegal, that political viewpoint does not exert much influence on how or why they vote.

- It’s also interesting that of the 38% of Americans who think abortion should be legal in most cases, 40% of them voted for Trump. Anyone who thinks that Trump supporters, or those who vote Republican more broadly, are all rabid pro-lifers, is (unfortunately) mistaken:

If we ever hope to outlaw abortion in this land, not only do we need to convince more people that abortion is wrong, but we must help them to understand why it matters so much and encourage them to translate their moral ideology into political action.

March 25, 2025

The Shroud of Turin

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Resurrection, Shroud of Turin, Theology[14] Comments

My podcast series on the resurrection is still going strong. I’ve recently started my last sub-series within the larger series, focused this time on the Shroud of Turin. If you have never heard of it before, it’s the purported burial cloth of Jesus Christ, bearing the image of a crucified man. Many Protestants have dismissed it as a fake Catholic relic, and most non-Christians have dismissed it as a medieval forgery due to carbon dating tests in the 1980s. However, interest in the Shroud has not gone away, and for good reason. There is much more to the story. In this sub-series, I’m examining the mountains of evidence for its authenticity, and I’ll address questions related to dating, and more.

My podcast series on the resurrection is still going strong. I’ve recently started my last sub-series within the larger series, focused this time on the Shroud of Turin. If you have never heard of it before, it’s the purported burial cloth of Jesus Christ, bearing the image of a crucified man. Many Protestants have dismissed it as a fake Catholic relic, and most non-Christians have dismissed it as a medieval forgery due to carbon dating tests in the 1980s. However, interest in the Shroud has not gone away, and for good reason. There is much more to the story. In this sub-series, I’m examining the mountains of evidence for its authenticity, and I’ll address questions related to dating, and more.March 17, 2025

Abortion, Nazis, and the Moral Hypocrisy of the Modern West

Posted by Jason Dulle under Abortion, Apologetics, Bioethics[9] Comments

We have a hard time understanding how the Germans allowed the Holocaust to take place. How could people so easily and so readily disregard the humanity of an entire group of people? How could they so callously kill millions of people? How could so many people who disagreed with the actions of the state stand by and do nothing? It’s not that hard to see how, really.

We have a hard time understanding how the Germans allowed the Holocaust to take place. How could people so easily and so readily disregard the humanity of an entire group of people? How could they so callously kill millions of people? How could so many people who disagreed with the actions of the state stand by and do nothing? It’s not that hard to see how, really.February 20, 2025

Apologetics is a Person-Specific Enterprise

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Tactics1 Comment

Apologetics is a person-specific enterprise. We are not trying to convince some generic Joe Blow, but specific individuals we encounter. Our apologetic should be tailored to meet the needs of the person we are dialoguing with.

For example, when someone tells you they don’t believe in God, the first thing you might do is ask them why. Their answer will help you to better direct your response. If the lone reason they reject the

existence of God is because of the problem of evil, it won’t do much good to hit them with every offensive apologetic argument for God’s existence, beginning with a cosmological argument. No. You need to go straight to a defensive apologetic, showing the logical consistency between theism and the existence of evil.

February 5, 2025

Contradictions in the Gospels?

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Bible, Bible Difficulties, Hermeneutics, Historical Jesus, Resurrection, Theology1 Comment

I posted back in October that I was starting a podcast series on the resurrection of Jesus. That series is still on-going. Right now I’m in the midst of a sub-series focused on explaining so-called contradictions in the Gospels, particularly in the empty tomb, resurrection, and post-mortem appearance narratives. I spent three weeks laying the foundation for how we ought to approach and understand Gospel differences. The episode to be released this Friday will start to explore specific examples of differences in the empty tomb narratives. Check it out wherever you get podcasts, or at https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com.

I posted back in October that I was starting a podcast series on the resurrection of Jesus. That series is still on-going. Right now I’m in the midst of a sub-series focused on explaining so-called contradictions in the Gospels, particularly in the empty tomb, resurrection, and post-mortem appearance narratives. I spent three weeks laying the foundation for how we ought to approach and understand Gospel differences. The episode to be released this Friday will start to explore specific examples of differences in the empty tomb narratives. Check it out wherever you get podcasts, or at https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com.

November 1, 2024

Pro-lifers split on how to vote Tuesday

Posted by Jason Dulle under Abortion, Bioethics, Politics[8] Comments

I’ve argued that pro-lifers should vote for Trump and the Republicans this November despite their recent backpedaling on the pro-life cause, because allowing the Democrats to win will result in many more babies being murdered. We should always act to save the most babies possible. Since more babies would be saved under Trump than under Harris, we should vote for Trump and the GOP.

I’ve argued that pro-lifers should vote for Trump and the Republicans this November despite their recent backpedaling on the pro-life cause, because allowing the Democrats to win will result in many more babies being murdered. We should always act to save the most babies possible. Since more babies would be saved under Trump than under Harris, we should vote for Trump and the GOP.

However, some pro-lifers have a different perspective. They argue that if we vote for Republicans next week simply because they are better than the Democrats, and they win, they’ll have little reason to revert the platform back to its strong pro-life position in 2026. If the GOP knows they can win elections without the pro-life vote, or if they know that pro-lifers will always vote for them because they are better than the Democrats on abortion, they will have no motivation to reverse course and re-adopt their former platform on abortion. Indeed, they are likely to deprioritize the issue going forward and continue making concessions to Leftists. So as a strategic move, these pro-lifers suggest that we let the Democrats win this election to teach the Republicans a lesson, namely that they need to be a strong and principled pro-life party if they ever hope to win another election.

October 9, 2024

Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus Series

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Historical Jesus, Resurrection, Shroud of Turin, Theology[3] Comments

I’ve begun a new podcast series on the historical evidence for the resurrection of Jesus. The series will not only cover the historical evidence for Jesus’ resurrection, but also explore alternative (naturalistic) explanations, the evidence for Jesus’ existence, the theological and practical significance of the resurrection, questions and objections, our own future resurrection, an examination of the Shroud of Turin, and a harmonization of the gospel accounts of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

I’ve begun a new podcast series on the historical evidence for the resurrection of Jesus. The series will not only cover the historical evidence for Jesus’ resurrection, but also explore alternative (naturalistic) explanations, the evidence for Jesus’ existence, the theological and practical significance of the resurrection, questions and objections, our own future resurrection, an examination of the Shroud of Turin, and a harmonization of the gospel accounts of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Listen wherever you get podcasts, or at https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com.

June 14, 2024

Theistic Arguments #8: An Existential Argument for God’s Existence

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Theistic ArgumentsLeave a Comment

The final argument for God’s existence in my podcast series, Does God Exist?, is a version of the existential argument. I argue that our deepest existential longings can only be explained by and satisfied by a theistic God: the desire for meaning and purpose in life, objective morality, immortality, free will, and love. People must either (1) believe there is a God who can satisfy our deepest longings or (2) believe there is no God and that our deepest longings are misguided and can never be satisfied.

The final argument for God’s existence in my podcast series, Does God Exist?, is a version of the existential argument. I argue that our deepest existential longings can only be explained by and satisfied by a theistic God: the desire for meaning and purpose in life, objective morality, immortality, free will, and love. People must either (1) believe there is a God who can satisfy our deepest longings or (2) believe there is no God and that our deepest longings are misguided and can never be satisfied.

The final episode just got published today. Check it out at https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com, or wherever you get podcasts.

June 3, 2024

Summary Arguments for God’s Existence #6 – Design Argument

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Design Argument, Theistic Arguments1 Comment

The design argument for God’s existence that I presented in my “Does God Exist?” podcast series could be succinctly summarized as “the universe looks designed because it was designed.”

The design argument for God’s existence that I presented in my “Does God Exist?” podcast series could be succinctly summarized as “the universe looks designed because it was designed.”

This could be fleshed out a bit more as follows: “Our universe exhibits a level of specificity and complexity that cannot be explained by chance or physical necessity, but only by a designing intelligence who transcends the universe and intentionally designed the universe to be inhabited by advanced lifeforms such as ourselves.”

I will offer one final version with a bit more detail: “There are many features of our universe that have to be just right for intelligent life to exist, including the initial conditions. The level of precision involved defies human comprehension. It can’t be explained by pure chance and there’s no reason to think it is due to physical necessity, so the best explanation is that these features were designed by a transcendent source. Design requires a designer > A designer requires intelligence > Intelligence requires a personal being = God.”

May 29, 2024

“The one who states his case first seems right, until the other comes and examines him” (ESV).

“The one who states his case first seems right, until the other comes and examines him” (ESV).

Many people have changed their beliefs because they heard someone make a persuasive case for some other point of view. Slow down. Don’t be so quick to change your beliefs. You need to examine their case more closely. If you can’t find anything wrong with their argument, ask others what they think of it. It’s particularly important that you ask someone who shares your current belief to examine this new point of view to see if they can find fault with the case being made. Or, see if you can find any formal debates on the matter. At the end of the day, you may discover that you were wrong and the other view is true, but more times than not, you’ll find that the case being made is not as strong as you first believed.

May 24, 2024

Thomas Aquinas’ Fourth and Fifth Ways

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Design Argument, Theistic Arguments[2] Comments

I just wrapped up my podcast discussion of Aquinas’ Five Ways by examining his Fourth and Fifth Ways. The Fourth Way argues that the grades of perfection we observe in the world can only be explained by the existence of a maximally perfect being. The Fifth Way argues for the existence of an intelligent being who guides everything towards their natural ends.

I just wrapped up my podcast discussion of Aquinas’ Five Ways by examining his Fourth and Fifth Ways. The Fourth Way argues that the grades of perfection we observe in the world can only be explained by the existence of a maximally perfect being. The Fifth Way argues for the existence of an intelligent being who guides everything towards their natural ends.

Check it out wherever you get your podcasts, or at https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com. Feel free to comment on the episode here as well.

May 20, 2024

Summary Arguments for God’s Existence #5 – Moral Argument

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Moral Argument, Theistic Arguments[2] Comments

There are so many ways to summarize the moral argument for God’s existence that I have a hard time boiling it down to just one or two. The most concise summary of the deductive moral argument for God’s existence could be stated as follows: “If objective morality exists (and it does), then God exists.”

There are so many ways to summarize the moral argument for God’s existence that I have a hard time boiling it down to just one or two. The most concise summary of the deductive moral argument for God’s existence could be stated as follows: “If objective morality exists (and it does), then God exists.”

This summary is so concise, however, that it does little more than state the logic of the argument. Why think that only God can explain morality? Here is a concise summary that also attempts to explain the connection in a bit more detail: “If God didn’t exist, there would be no moral laws and no moral obligations. But all of us know that moral laws exist and that we have an obligation to obey those laws, so God must exist. Laws require law-givers and obligations require persons to be obligated to. God is the source of moral values and the One to whom we are obligated.”

May 17, 2024

Thomas Aquinas’ Third Way: Argument from Contingency

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Theistic Arguments[2] Comments

My episode on Aquinas’ Third Way is now live. This is his argument from contingency. Aquinas argues that the existence of contingent beings can only be explained by the existence of a necessary being whose essence is identical to His existence.

My episode on Aquinas’ Third Way is now live. This is his argument from contingency. Aquinas argues that the existence of contingent beings can only be explained by the existence of a necessary being whose essence is identical to His existence.

Listen wherever you get podcasts, or at https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com.

May 13, 2024

Thomas Aquinas’ Second Way: Argument from Causality

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Theistic Arguments[5] Comments

I published my episode on Aquinas’ Second Way for God’s existence on Friday. Aquinas argues that a causal series can only be explained by a first, uncaused cause who is the source of all causation (which we call “God”).

I published my episode on Aquinas’ Second Way for God’s existence on Friday. Aquinas argues that a causal series can only be explained by a first, uncaused cause who is the source of all causation (which we call “God”).

I also covered a related argument (the existential proof) that Aquinas offers in a different work. The existential proof argues that things whose essence is distinct from their existence can only be explained by a being whose essence and existence are identical; i.e. a being who just is existence itself.

Give the episode a listen (https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com) and feel free to comment on the arguments presented on this blog post.

May 3, 2024

Theistic Arguments #7: Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Theistic Arguments[6] Comments

As I continue to examine additional arguments for God’s existence, I have finally come to Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways. The first episode on the First Way went live today.

As I continue to examine additional arguments for God’s existence, I have finally come to Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways. The first episode on the First Way went live today.

The First Way is Aquinas’ argument from motion. Aquinas argued that only God can explain why things change. Change can only be explained by a First, Unmoved Mover; i.e. a Being who is the ultimate source of all change, but is itself not changed by anything.

Check out this episode (and the ones to follow) wherever you get your podcasts, or from https://thinkingtobelieve.buzzsprout.com

April 23, 2024

No such thing as an “agnostic atheist”

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Atheism[45] Comments

It’s been common in the last couple of decades for atheists to attempt to redefine atheism as a “lack of belief in God” as opposed to “a belief that God does not exist.” I’ve examined the errors of this endeavor before (here, here, and here).

It’s been common in the last couple of decades for atheists to attempt to redefine atheism as a “lack of belief in God” as opposed to “a belief that God does not exist.” I’ve examined the errors of this endeavor before (here, here, and here).

From time-to-time, you’ll also see atheists getting even more creative with their labels. One that has interested me is the label “agnostic atheist.” This so-called position takes the redefinition of atheism as its starting point, and then adds to it the uncertainty that is implied by “agnostic.” An agnostic atheist, then, is someone who lacks a belief in God but does not know for sure whether God exists or not.*

April 16, 2024

Summary Arguments for God’s Existence #4 – Contingency Argument

Posted by Jason Dulle under Apologetics, Cosmological Argument, Theistic Arguments[2] Comments

Here is my most concise summary of the contingency argument for God’s existence: Things that don’t have to exist, but do, can only be explained by something that does have to exist.

Here is my most concise summary of the contingency argument for God’s existence: Things that don’t have to exist, but do, can only be explained by something that does have to exist.

Here is a version that is more fleshed out:

Things that did not have to exist, but do exist (contingent beings), require an explanation for why they exist, and that explanation must be found in some external cause. If everything that exists had an external cause, however, then there would have to be an infinite number of beings and an infinite regress of causes, and ultimately there would be no explanation for why anything that exists, exists. To explain why things that did not have to exist do exist, there must be at least one being that must exist and cannot not exist. This necessary being has being in Himself, and gives being to all other contingent beings.