Steven Cowan and Greg Welty argue contra Jerry Walls that compatibilism is consistent with Christianity.[1] What they question is the value of libertarian free will (the freedom to do other than what one, in fact, chooses to do, including evil). Why would God create human beings with the ability to choose evil? Libertarians typically argue that such is necessary in order to have genuine freedom, including the freedom to enter into a loving relationship with God. After all, if one could only choose A (the good), and could never choose B (the evil), then their “choice” of A is meaningless. The possibility of truly and freely choosing A requires at least the possibility of choosing B. The possibility of evil, then, is necessary for a free, loving relationship with God. It is logically impossible for God to create free creatures who are unable to choose anything other than A.

Steven Cowan and Greg Welty argue contra Jerry Walls that compatibilism is consistent with Christianity.[1] What they question is the value of libertarian free will (the freedom to do other than what one, in fact, chooses to do, including evil). Why would God create human beings with the ability to choose evil? Libertarians typically argue that such is necessary in order to have genuine freedom, including the freedom to enter into a loving relationship with God. After all, if one could only choose A (the good), and could never choose B (the evil), then their “choice” of A is meaningless. The possibility of truly and freely choosing A requires at least the possibility of choosing B. The possibility of evil, then, is necessary for a free, loving relationship with God. It is logically impossible for God to create free creatures who are unable to choose anything other than A.

Cowan and Wells ask, however, what would be wrong with God creating us in a way that made it impossible for us to desire or choose evil, and yet our choice would still be free. All that would be required is the presence of more than one good to choose from (A, C, D, E, F…). No matter what we choose, we could have chosen some other good, but never evil. This avoids the logical contradiction and preserves real freedom of choice. Cowan and Wells argue that such a world would be superior to our world since this possible world preserves libertarian free will, but lacks evil. In their assessment, there is no reason for the actual world if the value of libertarian free will (relationship with God, gives us freedom to choose the good, gives us the freedom to do otherwise) could be obtained without the possibility of evil. For the libertarian who wants to maintain that the actual world is superior to this possible world, they must maintain that the greatest value of libertarian freedom is that it gives us the opportunity to do evil. Why would God value our ability to do evil if He is good and hates evil? Why would God create a world in which libertarian freedom results in evil if He could have achieved all of the goals of libertarian freedom without evil?

(more…)

It’s amazing to me how we can interpret a passage to mean almost the exact opposite of its intended meaning simply because the intended meaning seems to conflict with our theology. A great example of this is Paul’s teaching in Romans 8:35-39:

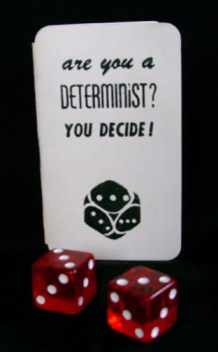

It’s amazing to me how we can interpret a passage to mean almost the exact opposite of its intended meaning simply because the intended meaning seems to conflict with our theology. A great example of this is Paul’s teaching in Romans 8:35-39: If God is omniscient, then He knows everything that will happen in the future – including everything you will ever do. God knows that on x date at time t1 you will stub your toe, and on q date at time t5 you will forget where you placed your keys. God has had such knowledge from eternity past. Since God cannot be mistaken, it is certain that you will stub your toe on x date at time t1 and forget your keys on q date at time t5. How, then, can our “choices” be free? Does God’s knowledge of the future eliminate free will, reducing us to mere actors who simply perform the parts of a cosmic play written for us by God from eternity past? Are we puppets with no control over our own destiny? Is our experience of free choice illusory? Darwinist, Robert Eberle, sums up the problem nicely:

If God is omniscient, then He knows everything that will happen in the future – including everything you will ever do. God knows that on x date at time t1 you will stub your toe, and on q date at time t5 you will forget where you placed your keys. God has had such knowledge from eternity past. Since God cannot be mistaken, it is certain that you will stub your toe on x date at time t1 and forget your keys on q date at time t5. How, then, can our “choices” be free? Does God’s knowledge of the future eliminate free will, reducing us to mere actors who simply perform the parts of a cosmic play written for us by God from eternity past? Are we puppets with no control over our own destiny? Is our experience of free choice illusory? Darwinist, Robert Eberle, sums up the problem nicely: Jesus said, “It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God” (Mt 19:24; Mk 10:25; Lk 18:25). Jesus said this after the young rich ruler refused Jesus’ call to discipleship because he was unwilling to give away all of his riches. Jesus’ point seems to be that people with wealth tend to trust in their wealth, making it difficult for them to place their trust in Christ.

Jesus said, “It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God” (Mt 19:24; Mk 10:25; Lk 18:25). Jesus said this after the young rich ruler refused Jesus’ call to discipleship because he was unwilling to give away all of his riches. Jesus’ point seems to be that people with wealth tend to trust in their wealth, making it difficult for them to place their trust in Christ.