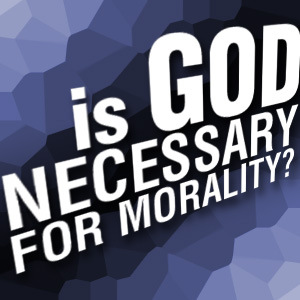

There are so many ways to summarize the moral argument for God’s existence that I have a hard time boiling it down to just one or two. The most concise summary of the deductive moral argument for God’s existence could be stated as follows: “If objective morality exists (and it does), then God exists.”

There are so many ways to summarize the moral argument for God’s existence that I have a hard time boiling it down to just one or two. The most concise summary of the deductive moral argument for God’s existence could be stated as follows: “If objective morality exists (and it does), then God exists.”

This summary is so concise, however, that it does little more than state the logic of the argument. Why think that only God can explain morality? Here is a concise summary that also attempts to explain the connection in a bit more detail: “If God didn’t exist, there would be no moral laws and no moral obligations. But all of us know that moral laws exist and that we have an obligation to obey those laws, so God must exist. Laws require law-givers and obligations require persons to be obligated to. God is the source of moral values and the One to whom we are obligated.”

Currently, I am in the midst of my

Currently, I am in the midst of my  The fifth argument I offer for God’s existence in my “Does God Exist?” podcast series is the moral argument. Moral arguments argue from the reality of morality to the existence of God. If morality is real > God is real.

The fifth argument I offer for God’s existence in my “Does God Exist?” podcast series is the moral argument. Moral arguments argue from the reality of morality to the existence of God. If morality is real > God is real. I told you about my relativism series in the last post. It is divided up into three sub-series: epistemological relativism (there is no truth at all), moral relativism (there is no moral truth), and religious relativism (there is no religious truth. I finished up the sub-series on epistemological relativism in December, and I’ve posted the first two episodes in the moral relativism sub-series in the last week.

I told you about my relativism series in the last post. It is divided up into three sub-series: epistemological relativism (there is no truth at all), moral relativism (there is no moral truth), and religious relativism (there is no religious truth. I finished up the sub-series on epistemological relativism in December, and I’ve posted the first two episodes in the moral relativism sub-series in the last week. There is a lot of confusion about what is meant by “moral relativism” and “moral objectivism/realism”

There is a lot of confusion about what is meant by “moral relativism” and “moral objectivism/realism” A view of morality you’ll hear a lot in the public square is social contract theory. Contractarianism holds that “morality rests on a tacit agreement between rationally self-interested individuals to abide by certain rules because it is to their mutual advantage to do so.”1 There is nothing intrinsically wrong with murder, rape, or torture, for example, but since rational self-interested persons do not want these things being done to them, they agree to extend the same courtesy to others.2 Philosopher, Edward Feser, offers at least six helpful criticisms of Contractarianism:

A view of morality you’ll hear a lot in the public square is social contract theory. Contractarianism holds that “morality rests on a tacit agreement between rationally self-interested individuals to abide by certain rules because it is to their mutual advantage to do so.”1 There is nothing intrinsically wrong with murder, rape, or torture, for example, but since rational self-interested persons do not want these things being done to them, they agree to extend the same courtesy to others.2 Philosopher, Edward Feser, offers at least six helpful criticisms of Contractarianism:  When Christians offer arguments for the existence of God based on the beginning of the universe or the objective nature of morality, some atheists will respond by asking, “Why can’t we just say we don’t know what caused the universe or what the objective source of morality is?” How might a thoughtful Christian respond?

When Christians offer arguments for the existence of God based on the beginning of the universe or the objective nature of morality, some atheists will respond by asking, “Why can’t we just say we don’t know what caused the universe or what the objective source of morality is?” How might a thoughtful Christian respond? Theists argue that God is the best explanation for objective moral truths. Atheists typically appeal to the Euthyphro Dilemma (ED) to show that God cannot be the foundation for morality. The ED asks whether something is good only because God wills it as such, or if God wills something because it is good. If something is good only because God considers it good, then goodness seems arbitrary and relative to God’s desires. If He had so chosen, murder could have been right and truth-telling could have been wrong. On the other hand, if God wills the good because it is inherently good, then goodness would be a standard that exists outside of God. He is subject to the moral law just as we are.

Theists argue that God is the best explanation for objective moral truths. Atheists typically appeal to the Euthyphro Dilemma (ED) to show that God cannot be the foundation for morality. The ED asks whether something is good only because God wills it as such, or if God wills something because it is good. If something is good only because God considers it good, then goodness seems arbitrary and relative to God’s desires. If He had so chosen, murder could have been right and truth-telling could have been wrong. On the other hand, if God wills the good because it is inherently good, then goodness would be a standard that exists outside of God. He is subject to the moral law just as we are.