“The one who states his case first seems right, until the other comes and examines him” (ESV).

“The one who states his case first seems right, until the other comes and examines him” (ESV).

Many people have changed their beliefs because they heard someone make a persuasive case for some other point of view. Slow down. Don’t be so quick to change your beliefs. You need to examine their case more closely. If you can’t find anything wrong with their argument, ask others what they think of it. It’s particularly important that you ask someone who shares your current belief to examine this new point of view to see if they can find fault with the case being made. Or, see if you can find any formal debates on the matter. At the end of the day, you may discover that you were wrong and the other view is true, but more times than not, you’ll find that the case being made is not as strong as you first believed.

Scientists could never discover that free will does not exist via scientific experimentation, because in a deterministic world, the result of the experiment would, itself, be determined. The conclusion that there is no such thing as free will would not be arrived at because the scientists chose to set up the experiment in a good way and reasoned correctly about the data they received. Instead, physics would determine both the study’s structure and conclusions. As such, the conclusion cannot be trusted.

Scientists could never discover that free will does not exist via scientific experimentation, because in a deterministic world, the result of the experiment would, itself, be determined. The conclusion that there is no such thing as free will would not be arrived at because the scientists chose to set up the experiment in a good way and reasoned correctly about the data they received. Instead, physics would determine both the study’s structure and conclusions. As such, the conclusion cannot be trusted. We tend to trust the experts. The impulse is right because the experts have more knowledge and expertise in the subject than we do. They know the nuances. But when the experts claim to be above critique by non-experts, that’s a problem. When they say (in so many words) “you can’t evaluate my claims because I am the smart one and you are the dummy,” they are presenting an empty appeal to authority. The experts often differ among themselves, so we have reason to question the experts. After all, they can’t all be right. The only way to determine who is right is to question the experts.

We tend to trust the experts. The impulse is right because the experts have more knowledge and expertise in the subject than we do. They know the nuances. But when the experts claim to be above critique by non-experts, that’s a problem. When they say (in so many words) “you can’t evaluate my claims because I am the smart one and you are the dummy,” they are presenting an empty appeal to authority. The experts often differ among themselves, so we have reason to question the experts. After all, they can’t all be right. The only way to determine who is right is to question the experts. Greg Koukl delivered a lecture at the 2006 Master’s Series in Christian Thought on the topic, “Truth is a Strange Sort of Fiction: The Challenge from the Emergent Church.” While the Emergent Church has morphed into the Progressive Church, the information is just as relevant today as it was in 2006.

Greg Koukl delivered a lecture at the 2006 Master’s Series in Christian Thought on the topic, “Truth is a Strange Sort of Fiction: The Challenge from the Emergent Church.” While the Emergent Church has morphed into the Progressive Church, the information is just as relevant today as it was in 2006. If God is omniscient, then He knows everything that will happen in the future – including everything you will ever do. God knows that on x date at time t1 you will stub your toe, and on q date at time t5 you will forget where you placed your keys. God has had such knowledge from eternity past. Since God cannot be mistaken, it is certain that you will stub your toe on x date at time t1 and forget your keys on q date at time t5. How, then, can our “choices” be free? Does God’s knowledge of the future eliminate free will, reducing us to mere actors who simply perform the parts of a cosmic play written for us by God from eternity past? Are we puppets with no control over our own destiny? Is our experience of free choice illusory? Darwinist, Robert Eberle, sums up the problem nicely:

If God is omniscient, then He knows everything that will happen in the future – including everything you will ever do. God knows that on x date at time t1 you will stub your toe, and on q date at time t5 you will forget where you placed your keys. God has had such knowledge from eternity past. Since God cannot be mistaken, it is certain that you will stub your toe on x date at time t1 and forget your keys on q date at time t5. How, then, can our “choices” be free? Does God’s knowledge of the future eliminate free will, reducing us to mere actors who simply perform the parts of a cosmic play written for us by God from eternity past? Are we puppets with no control over our own destiny? Is our experience of free choice illusory? Darwinist, Robert Eberle, sums up the problem nicely: When Christians offer arguments for the existence of God based on the beginning of the universe or the objective nature of morality, some atheists will respond by asking, “Why can’t we just say we don’t know what caused the universe or what the objective source of morality is?” How might a thoughtful Christian respond?

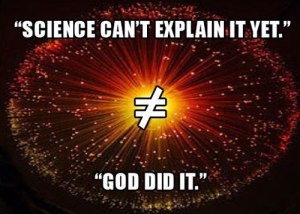

When Christians offer arguments for the existence of God based on the beginning of the universe or the objective nature of morality, some atheists will respond by asking, “Why can’t we just say we don’t know what caused the universe or what the objective source of morality is?” How might a thoughtful Christian respond?