Part of our theodicy for the problem of evil includes the point that it was logically impossible for God to create a world in which humans enjoyed free will (a good thing), and yet were unable to use that freedom to choose evil as well as the good. I accept that as true, and yet Christianity proclaims there is coming a day in which there will be a world consisting of humans with libertarian free-will, who will never choose evil: heaven. The future hope of Christians seems to undermine one of the central premises in our theodicy. Can this be reconciled?

Some have suggested that we will not sin in heaven because we’ll be in the beatific presence of God. Presumably, the angels exist in the beatific presence of God, and yet many of the angels chose to rebel against God in that state. This alone, then, cannot explain why humans won’t sin in heaven.

Others have suggested that we will not sin in heaven because God will glorify our humanity. But this is not a solution; it is an admission of the problem. Glorification is being put forward, not to show that such a world cannot exist, but rather to explain how it will become a reality. If in the future God is able—through glorification—to make human beings such that they have free will, and yet will not choose evil, then it falsifies the claim that God cannot create a world in which humans enjoy libertarian free will, and yet never choose evil. Indeed, He will do so in the future. In light of such, we might ask why God did not do this from the onset. Why didn’t He create humans in a glorified state to begin with, if glorified humans can exercise free will and yet not choose evil?

(more…)

Evangelism is scary for many people, including myself. Many Christians find it difficult to start a discussion on spiritual things. Others fear that they’ll be pummeled with objections to the faith that they don’t know how to answer. Many fear rejection. As a result, we’ve invented new methods of “evangelism” that don’t require us to actually talk to anyone. I’m thinking of “friendship evangelism” and “love evangelism” in particular.

Evangelism is scary for many people, including myself. Many Christians find it difficult to start a discussion on spiritual things. Others fear that they’ll be pummeled with objections to the faith that they don’t know how to answer. Many fear rejection. As a result, we’ve invented new methods of “evangelism” that don’t require us to actually talk to anyone. I’m thinking of “friendship evangelism” and “love evangelism” in particular. Theists argue that God is the best explanation for objective moral truths. Atheists typically appeal to the Euthyphro Dilemma (ED) to show that God cannot be the foundation for morality. The ED asks whether something is good only because God wills it as such, or if God wills something because it is good. If something is good only because God considers it good, then goodness seems arbitrary and relative to God’s desires. If He had so chosen, murder could have been right and truth-telling could have been wrong. On the other hand, if God wills the good because it is inherently good, then goodness would be a standard that exists outside of God. He is subject to the moral law just as we are.

Theists argue that God is the best explanation for objective moral truths. Atheists typically appeal to the Euthyphro Dilemma (ED) to show that God cannot be the foundation for morality. The ED asks whether something is good only because God wills it as such, or if God wills something because it is good. If something is good only because God considers it good, then goodness seems arbitrary and relative to God’s desires. If He had so chosen, murder could have been right and truth-telling could have been wrong. On the other hand, if God wills the good because it is inherently good, then goodness would be a standard that exists outside of God. He is subject to the moral law just as we are. When something bad happens, it’s common for people to offer the encouragement that “everything happens for a reason.” Is it really true, however, that everything that happens, happens for a reason? To answer that question we need to explore what we mean by “everything,” “for” and “reason.”

When something bad happens, it’s common for people to offer the encouragement that “everything happens for a reason.” Is it really true, however, that everything that happens, happens for a reason? To answer that question we need to explore what we mean by “everything,” “for” and “reason.” The resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead was the central message of the early church and the basis of Christian hope. But why should we believe that a man was raised from the dead 2000 years ago when we were not there to witness it, and when our uniform experience says that dead people always stay dead? While many people think the resurrection of Jesus is something you either choose to believe or choose to reject based on your personal religious tastes, the fact of the matter is that there are good, objective, historical reasons to believe that Jesus rose from the dead.

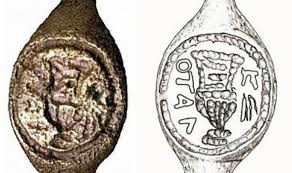

The resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead was the central message of the early church and the basis of Christian hope. But why should we believe that a man was raised from the dead 2000 years ago when we were not there to witness it, and when our uniform experience says that dead people always stay dead? While many people think the resurrection of Jesus is something you either choose to believe or choose to reject based on your personal religious tastes, the fact of the matter is that there are good, objective, historical reasons to believe that Jesus rose from the dead. Another clay seal (bulla) bearing the name of a Biblical person has been unearthed in the City of David. The tiny clay seal was found in the remains of a large housing structure that had been destroyed by fire in the sixth century B.C. The seal reads, “[belonging to] Nathan-Melech, Servant of the King.” Nathan-Melech appears once in the Bible, in 2 Kings 23:11, and is said to be an official in the court of King Josiah.

Another clay seal (bulla) bearing the name of a Biblical person has been unearthed in the City of David. The tiny clay seal was found in the remains of a large housing structure that had been destroyed by fire in the sixth century B.C. The seal reads, “[belonging to] Nathan-Melech, Servant of the King.” Nathan-Melech appears once in the Bible, in 2 Kings 23:11, and is said to be an official in the court of King Josiah.  While there is much discussion regarding the fidelity of the transmission of the NT text, very little attention is given to the OT. I’ve long been looking for a good book dedicated to OT textual criticism, written from the perspective of a conservative text critic, so I was happy to come across John F. Brug’s

While there is much discussion regarding the fidelity of the transmission of the NT text, very little attention is given to the OT. I’ve long been looking for a good book dedicated to OT textual criticism, written from the perspective of a conservative text critic, so I was happy to come across John F. Brug’s  I recently finished Everett Ferguson’s

I recently finished Everett Ferguson’s  In the parting words of Paul’s first letter to the church at Thessalonica, he admonished them with several imperatives, including “pray without ceasing” (1 Thes 5:17).

In the parting words of Paul’s first letter to the church at Thessalonica, he admonished them with several imperatives, including “pray without ceasing” (1 Thes 5:17). Probably the most-cited argument against the existence of a theistic God is the logical form of the problem of evil, which argues that the existence of an all-good and all-powerful God is logically incompatible with the existence of evil because an all-good God would want to prevent evil and an all-powerful God could prevent evil, and yet evil exists. From this, it follows that God is not all-powerful, not all-good, or more likely does not exist at all. There could be a world in which God exists, or there could be a world in which evil exists, but there can be no world in which both God and evil exist. Since it’s empirically evident that evil exists, God does not.

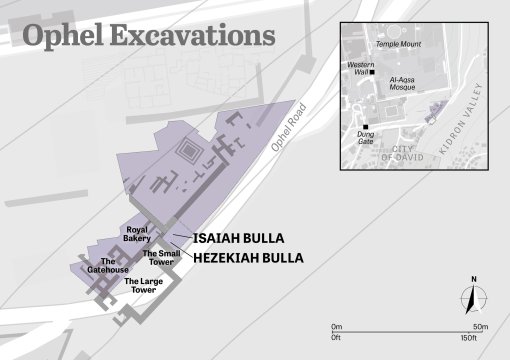

Probably the most-cited argument against the existence of a theistic God is the logical form of the problem of evil, which argues that the existence of an all-good and all-powerful God is logically incompatible with the existence of evil because an all-good God would want to prevent evil and an all-powerful God could prevent evil, and yet evil exists. From this, it follows that God is not all-powerful, not all-good, or more likely does not exist at all. There could be a world in which God exists, or there could be a world in which evil exists, but there can be no world in which both God and evil exist. Since it’s empirically evident that evil exists, God does not. A few weeks ago, a

A few weeks ago, a  Jesus said, “It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God” (Mt 19:24; Mk 10:25; Lk 18:25). Jesus said this after the young rich ruler refused Jesus’ call to discipleship because he was unwilling to give away all of his riches. Jesus’ point seems to be that people with wealth tend to trust in their wealth, making it difficult for them to place their trust in Christ.

Jesus said, “It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God” (Mt 19:24; Mk 10:25; Lk 18:25). Jesus said this after the young rich ruler refused Jesus’ call to discipleship because he was unwilling to give away all of his riches. Jesus’ point seems to be that people with wealth tend to trust in their wealth, making it difficult for them to place their trust in Christ. A 69 year old Dutch man, Emile Ratelband, is

A 69 year old Dutch man, Emile Ratelband, is

We often speak of the need to “forgive yourself.” While I understand what is meant by this phrase, it is unintelligible on the Christian worldview. People speak of the need to forgive themselves in the context of feeling guilt for something they did (or failed to do). They recognize the need to eliminate this guilt and get on with their life – to stop beating themselves up for their failure.

We often speak of the need to “forgive yourself.” While I understand what is meant by this phrase, it is unintelligible on the Christian worldview. People speak of the need to forgive themselves in the context of feeling guilt for something they did (or failed to do). They recognize the need to eliminate this guilt and get on with their life – to stop beating themselves up for their failure. In the

In the  Have you ever tried striking up a conversation with someone about the existence of God only to find that they have no interest in the question? Trying to continue the conversation is like trying to talk to a two year old about quantum mechanics. Strategically, you must find a way to get the unbeliever to see that the question of God’s existence is relevant to his/her life. I think the most effective approach is to appeal to common existential questions that every human wonders about. This could include:

Have you ever tried striking up a conversation with someone about the existence of God only to find that they have no interest in the question? Trying to continue the conversation is like trying to talk to a two year old about quantum mechanics. Strategically, you must find a way to get the unbeliever to see that the question of God’s existence is relevant to his/her life. I think the most effective approach is to appeal to common existential questions that every human wonders about. This could include: Skeptics of Christianity often try to undermine the truth of Christianity by pointing to supposed errors or contradictions in the Bible. As a result, some Christians have abandoned the faith, while others remain shaken in their faith. This is unfortunate because the skeptics’ approach is fundamentally flawed.

Skeptics of Christianity often try to undermine the truth of Christianity by pointing to supposed errors or contradictions in the Bible. As a result, some Christians have abandoned the faith, while others remain shaken in their faith. This is unfortunate because the skeptics’ approach is fundamentally flawed.